Festa fékk þær Birtu Kristínu Helgadóttur, sviðsstjóra Orku hjá EFLU og Tinnu Hallgrímsdóttur, sérfræðing í loftslagsáhættu og sjálfbærni hjá Seðlabanka Íslands til þess að skrifa sitthvora samantektina eftir COP29 í Baku, Aserbaísjan.

2.12.24

Samantekt eftir COP frá Tinnu Hallgrímsdóttur

Þrefað um loftslagsfjármögnun á COP29

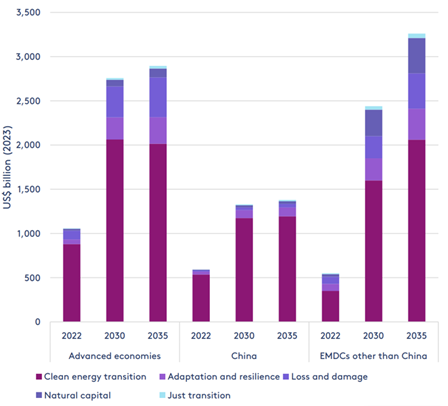

The world faces unprecedented investment needs and opportunities for climate action, as outlined in the report by Nicholas Stern et al., a group of senior economists, released ahead of COP29. To achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement, there is an urgent need to finance action in five main categories (see breakdown in Figure 1):

- Energy exchange

- Restoration and protection of ecosystems and sustainable agriculture

- Adaptation and increased resilience to climate change

- Losses and damages that countries suffer from climate change

- Just transition to a low-carbon economy

Fjárfestingarþörfin nemur a.m.k. 7 billjónum (7 milljón milljónum) bandaríkjadala árlega fram að 2035, þar af a.m.k. 2,6 til þróaðra ríkja, 1,3 til Kína og 3,1 til nýmarkaðs- og þróunarríkja að Kína undanskildu (Mynd 1).

Investment needs to be scaled up rapidly in all countries, but the situation is most urgent in emerging and developing countries, with the exception of China. These countries have the greatest need for increased investment in energy transition, are the most vulnerable to the consequences of climate change, and possess the vast majority of the world's natural resources and biodiversity.

If climate action in emerging and developing countries is not financed, humanity has no hope of achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement, as Article 9 of the agreement states that developed countries must provide funding to developing countries for mitigation and adaptation.

In light of this, the parties to the Convention agreed, alongside the Paris Agreement at COP21, to establish a new climate finance target for 2025, which was to replace the previous target of $100 billion per year.

The previous target of $100 billion per year was politically determined and not based on a needs analysis. It was therefore decided that the new target should take into account the needs and priorities of developing countries.

It was therefore at the recent Conference of the Parties, specifically COP29, held in Baku, Azerbaijan in November 2024, that a new collective goal on climate finance (New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance) was to be adopted, which would replace the previous goal starting in 2025.

As noted above, the investment needs for climate action in emerging market and developing countries excluding China are at least $3.2 trillion annually by 2035. Domestic capital can cover part of this need, but at least $1.3 trillion annually needs to come from external capital by 2035.

Það var því samningsaðilum ljóst að til að ná raunverulegum árangri í viðræðum um nýja loftslagsfjármögnunarmarkmiðið þyrfti að fara úr milljörðum dala upp í billjónir dala.

The final result was therefore a great disappointment for developing countries, but it was agreed that developed countries would take the lead in providing 300 billion US dollars annually to developing countries for climate action by 2035.

Likewise, a call was adopted for Member States to cooperate in scaling up climate finance to developing countries to reach $1.3 trillion annually by 2035 from public and private sources (Figure 2 [Article 7]).

En það var ekki einungis fjárhæðin sem varð að deilumáli. Einnig var þrefað um hvaða ríki skyldu veita fjármagn sem félli undir markmiðið, hvers kyns fjármagn um yrði að ræða og hver tímaramminn yrði.

The previous target of $100 billion per year outlined which countries should provide funding to meet the target. This was based on the 1992 UN Climate Change Convention, which defined countries that were OECD members at the time as developed (and are listed in Annex II). Much has changed since 1992, and developed countries have argued that relatively wealthy emerging market countries such as China and the United Arab Emirates should also provide funding to meet the target, as their emissions have increased significantly since 1992 and many of them have become wealthier. This is opposed by developing countries, who argue that developed countries are trying to evade responsibility. During the conference, various versions of how to determine which countries should provide funding emerged in draft texts.

fjármagn, til dæmis að skipta löndum upp eftir losun (sögulegri og/eða núverandi) og vergri landsframleiðslu. Lokaniðurstaðan var að hrófla ekki við þeirri skiptingu sem stillt var upp í Loftslagssamningnum árið 1992, en opna þó á þann möguleika að ríki sem ekki væru skilgreind sem þróuð gætu einnig veitt fjármagn sem félli undir markmiðið án þess að missa stöðu sína sem þiggjandi fjármagns (Mynd 3 [9. og 10. gr]). Þróuð ríki eiga þó að vera í forystu um að veita loftslagsfjármagn sem tengist 300 ma. dala markmiðinu (Mynd 3 [8. gr]).

Gerð fjármagns skipti líka höfuðmáli í samningsviðræðunum.

Meirihluti loftslagsfjármagns er í formi lána, þar með talið stór hluti í lánum án ívilnana. Það kemur sér illa fyrir þróunarlönd sem eru mörg hver afar skuldsett, en skuldsetning lágtekjuríkja hefur

aukist verulega á seinasta áratug. Þau hafa því kallað eftir því að fjármagn sé í formi styrkja eða lána með ívilnunum (þ.e.a.s. lána með lægri vöxtum og meiri sveigjanleika). Sum þróunarríki töluðu fyrir því að fjármagn yrði framtalið í styrkja-ígildum, þ.e.a.s. að lán myndu telja minna en ella. Þróuð ríki hafa hinsvegar talað fyrir því að stækka mengi gerðar þess fjármagns sem tengist markmiðinu, og vilja að þar undir falli bæði innlent og erlent fjármagn, opinbert og einkafjármagn og fjárfestingar.

The conclusion was to not deviate from the definition of the previous goal, as it covers a variety of sources of finance, including public and private finance, bilateral and international finance, and development banks (Figure 3 [Article 8(a) and (c)]). The demands of developing countries for limits on non-concessional loans or for a certain proportion to be in the form of grants were not included in the text.

The timeframe of the target is also crucial. Many developing countries argued for the target to take effect from 2025 or 2026, i.e. that the target would have to be achieved immediately next year or the year after that and would be valid until 2030 or 2035. This undoubtedly reflects the distrust that many developing countries have towards developed countries, since the previous target of 100 billion dollars per year was not achieved until two years behind schedule, and that without compensation. The conclusion, however, was that the target would have to be achieved by 2035, i.e. that resources should be scaled up annually until the amount was reached in 2035 at the latest.

Mörg sneru því vonsvikin til baka til sinna heimalanda frá þessu 29. aðildarríkjaþingi Loftslagssamnings Sameinuðu þjóðanna. Ljóst er að betur má ef duga skal. Þrjú hundruð milljarðar bandaríkjadala árlega komast ekki nálægt því að uppfylla ytri fjárfestingarþörf loftslagsaðgerða í þróunarlöndum og óljóst er hvort ákallið um 1,3 billjónir dala heildarframlag úr hinum ýmsu áttum muni kalla fram það gríðarlega stökk í flæði einkafjármagns sem þörf er á. Raunin er sú að sama hvernig við skiptum upp heimsbyggðinni sitjum við öll í sömu súpunni þegar kemur að þeirri hnattrænu ógn sem loftslagsbreytingar boða. Vanfjármögnun loftslagsaðgerða í nýmarkaðs- og þróunarríkjum felur ekki einungis í sér staðbundin áhrif heldur verður þeirra vart víða um heim, m.a. vegna rofs og breytinga á aðfangakeðjum af völdum loftslagsbreytinga og fjölgun loftslagsflóttafólks. Líkt og António Guterres, aðalritari Sameinuðu þjóðanna, orðaði það í opnunarávarpi sínu á COP29, „Heimsbyggðin verður að borga gjaldið; annars mun mannkynið gjalda þess. Fjármögnun loftslagsaðgerða er ekki góðgerðarstarfsemi heldur fjárfesting“.